- Home

- Kamel Daoud

The Meursault Investigation

The Meursault Investigation Read online

Copyright © Éditions Barzakh, Alger, 2013

Copyright © Actes Sud, 2014

Originally published in French as Meursault, contre-enquête by Éditions Barzakh in Algeria in 2013, and by Actes Sud in France in 2014.

Translation copyright © Other Press, 2015

An excerpt from this novel was first published in the April 6, 2015 issue of The New Yorker.

The author has quoted and occasionally adapted certain passages from The Stranger by Albert Camus, translated by Matthew Ward (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1988). The lyrics on this page are from “Malou Khouya” by Khaled.

Production editor: Yvonne E. Cárdenas.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from Other Press LLC, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. For information write to Other Press LLC, 2 Park Avenue, 24th Floor, New York, NY 10016. Or visit our Web site: www.otherpress.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Daoud, Kamel.

[Meursault, contre-enquête. English]

The Meursault investigation / Kamel Daoud; translated by John Cullen.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-59051-751-2 (paperback) — ISBN 978-1-59051-752-9 (e-book)

1. Arabs — Fiction. 2. Camus, Albert, 1913–1960. Étranger — Fiction. 3. Algeria — Fiction. 4. Psychological fiction. 5. Political fiction. I. Cullen, John, 1942– translator. II. Title.

PQ3989.3.D365M4813 2015

843’.92 — dc23

2015010736

Publisher’s Note:

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

v3.1

For Aïda.

For Ikbel.

My open eyes.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter VII

Chapter VIII

Chapter IX

Chapter X

Chapter XI

Chapter XII

Chapter XIII

Chapter XIV

Chapter XV

About the Author

The hour of crime does not strike at the

same time for every people. This

explains the permanence of history.

— E. M. CIORAN

Syllogismes de l’amertume

I

Mama’s still alive today.

She doesn’t say anything now, but there are many tales she could tell. Unlike me: I’ve rehashed this story in my head so often, I almost can’t remember it anymore.

I mean, it goes back more than half a century. It happened, and everyone talked about it. People still do, but they mention only one dead man, they feel no compunction about doing that, even though there were two of them, two dead men. Yes, two. Why does the other one get left out? Well, the original guy was such a good storyteller, he managed to make people forget his crime, whereas the other one was a poor illiterate God created apparently for the sole purpose of taking a bullet and returning to dust — an anonymous person who didn’t even have the time to be given a name.

I’ll tell you this up front: The other dead man, the murder victim, was my brother. There’s nothing left of him. There’s only me, left to speak in his place, sitting in this bar, waiting for condolences no one’s ever going to offer. Laugh if you want, but this is more or less my mission: I peddle offstage silence, trying to sell my story while the theater empties out. As a matter of fact, that’s the reason why I’ve learned to speak this language, and to write it too: so I can speak in the place of a dead man, so I can finish his sentences for him. The murderer got famous, and his story’s too well written for me to get any ideas about imitating him. He wrote in his own language. Therefore I’m going to do what was done in this country after Independence: I’m going to take the stones from the old houses the colonists left behind, remove them one by one, and build my own house, my own language. The murderer’s words and expressions are my unclaimed goods. Besides, the country’s littered with words that don’t belong to anyone anymore. You see them on the façades of old stores, in yellowing books, on people’s faces, or transformed by the strange creole decolonization produces.

So it’s been quite some time since the murderer died, and much too long since my brother ceased to exist for everyone but me. I know, you’re eager to ask the type of questions I hate, but please listen to me instead, please give me your attention, and by and by you’ll understand. This is no normal story. It’s a story that begins at the end and goes back to the beginning. Yes, like a school of salmon swimming upstream. I’m sure you’re like everyone else, you’ve read the tale as told by the man who wrote it. He writes so well that his words are like precious stones, jewels cut with the utmost precision. A man very strict about shades of meaning, your hero was; he practically required them to be mathematical. Endless calculations, based on gems and minerals. Have you seen the way he writes? He’s writing about a gunshot, and he makes it sound like poetry! His world is clean, clear, exact, honed by morning sunlight, enhanced with fragrances and horizons. The only shadow is cast by “the Arabs,” blurred, incongruous objects left over from “days gone by,” like ghosts, with no language except the sound of a flute. I tell myself he must have been fed up with wandering around in circles in a country that wanted nothing to do with him, whether dead or alive. The murder he committed seems like the act of a disappointed lover unable to possess the land he loves. How he must have suffered, poor man! To be the child of a place that never gave you birth …

I too have read his version of the facts. Like you and millions of others. And everyone got the picture, right from the start: He had a man’s name; my brother had the name of an incident. He could have called him “Two P.M.,” like that other writer who called his black man “Friday.” An hour of the day instead of a day of the week. Two in the afternoon, that’s good. Zujj in Algerian Arabic, two, the pair, him and me, the unlikeliest twins, somehow, for those who know the story of the story. A brief Arab, technically ephemeral, who lived for two hours and has died incessantly for seventy years, long after his funeral. It’s like my brother Zujj has been kept under glass. And even though he was a murder victim, he’s always given some vague designation, complete with reference to the two hands of a clock, over and over again, so that he replays his own death, killed by a bullet fired by a Frenchman who just didn’t know what to do with his day and with the rest of the world, which he carried on his back.

And again! Whenever I go over this story in my head, I get angry — at least, I do whenever I have the strength. So the Frenchman plays the dead man and goes on and on about how he lost his mother, and then about how he lost his body in the sun, and then about how he lost a girlfriend’s body, and then about how he went to church and discovered that his God had deserted the human body, and then about how he sat up with his mother’s corpse and his own, et cetera. Good God, how can you kill someone and then take even his own death away from him? My brother was the one who got shot, not him! It was Musa, not Meursault, see? There’s something I find stunning, and it’s that nobody — not ev

en after Independence — nobody at all ever tried to find out what the victim’s name was, or where he lived, or what family he came from, or whether he had children. Nobody. Everyone was knocked out by the perfect prose, by language capable of giving air facets like diamonds, and everyone declared their empathy with the murderer’s solitude and offered him their most learned condolences. Who knows Musa’s name today? Who knows what river carried him to the sea, which he had to cross on foot, alone, without his people, without a magic staff? Who knows whether Musa had a gun, a philosophy, or a sunstroke?

Who was Musa? He was my brother. That’s what I’m getting at. I want to tell you the story Musa was never able to tell. When you opened the door of this bar, you opened a grave, my young friend. Do you happen to have the book in your schoolbag there? Good. Play the disciple and read me the first page or so …

So. Did you understand? No? I’ll explain it to you. After his mother dies, this man, this murderer, finds himself without a country and falls into idleness and absurdity. He’s a Robinson Crusoe who thinks he can change his destiny by killing his Friday but instead discovers he’s trapped on an island and starts banging on like a self-indulgent parrot. “Poor Meursault, where are you?” Shout out those words a few times and they’ll seem less ridiculous, I promise. And I’m asking that question for your sake. I know the book by heart, I can recite it to you like the Koran. That story — a corpse wrote it, not a writer. You can tell by the way he suffers from the sun and gets dazzled by colors and has no opinion on anything except the sun, the sea, and the surrounding rocks. From the very beginning, you can sense that he’s looking for my brother. And in fact, he seeks him out, not so much to meet him as to never have to. What hurts me every time I think about it is that he killed him by passing over him, not by shooting him. You know, his crime is majestically nonchalant. It made any subsequent attempt to present my brother as a shahid, a martyr, impossible. The martyr came too long after the murder. In the interval, my brother rotted in his grave and the book obtained its well-known success. And afterward, therefore, everybody bent over backward to prove there was no murder, just sunstroke.

Ha, ha! What are you drinking? In these parts, you get offered the best liquors after your death, not before. And that’s religion, my brother. Drink up — in a few years, after the end of the world, the only bar still open will be in Paradise.

I’m going to outline the story before I tell it to you. A man who knows how to write kills an Arab who, on the day he dies, doesn’t even have a name, as if he’d hung it on a nail somewhere before stepping onto the stage. Then the man begins to explain that his act was the fault of a God who doesn’t exist and that he did it because of what he’d just realized in the sun and because the sea salt obliged him to shut his eyes. All of a sudden, the murder is a deed committed with absolute impunity and wasn’t a crime anyway because there’s no law between noon and two o’clock, between him and Zujj, between Meursault and Musa. And for seventy years now, everyone has joined in to disappear the victim’s body quickly and turn the place where the murder was committed into an intangible museum. What does “Meursault” mean? Meurt seul, dies alone? Meurt sot, dies a fool? Never dies? My poor brother had no say in this story. And that’s where you go wrong, you and all your predecessors. The absurd is what my brother and I carry on our backs or in the bowels of our land, not what the other was or did. Please understand me, I’m not speaking in either sorrow or anger. I’m not even going to play the mourner. It’s just that … it’s just what? I don’t know. I think I’d just like justice to be done. That may seem ridiculous at my age … But I swear it’s true. I don’t mean the justice of the courts, I mean the justice that comes when the scales are balanced. And I’ve got another reason besides: I want to pass away without being pursued by a ghost. I think I can guess why people write true stories. Not to make themselves famous but to make themselves more invisible, and all the while clamoring for a piece of the world’s true core.

Drink up and look out the window — you’d think this country was an aquarium. Right, right, but it’s your fault too, my friend; your curiosity provokes me. I’ve been waiting for you for years, and if I can’t write my book, at least I can tell you the story, can’t I? A man who’s drinking is always dreaming about a man who’ll listen. That’s today’s bit of wisdom, write it down in your notebook …

It’s simple: The story we’re talking about should be rewritten, in the same language, but from right to left. That is, starting when the Arab’s body was still alive, going down the narrow streets that led to his demise, giving him a name, right up until the bullet hit him. So one reason for learning this language was to tell this story for my brother, the friend of the sun. Seems unlikely to you? You’re wrong. I had to find the response nobody wanted to give me when I needed it. You drink a language, you speak a language, and one day it owns you; and from then on, it falls into the habit of grasping things in your place, it takes over your mouth like a lover’s voracious kiss. I knew someone who learned to write in French because one day his illiterate father received a telegram no one could decipher. This was in the days when your hero was still alive and the colonists were still running the show. The telegram lay rotting in this fellow’s pocket for a week before somebody read it to him. In three lines, it informed him of his mother’s death, somewhere deep in the treeless country. He told me, “I learned to write for my father, and I learned to write so that such a thing could never happen again. I’ll never forget his anger with himself, and his eyes begging me to help him.” Basically, my reason’s the same as his. Well, go on, read some more, even if the whole thing’s written in my head. Every night, my brother Musa, alias Zujj, arises from the Realm of the Dead and pulls my beard and cries, “Oh my brother Harun, why did you let this happen? I’m not a sacrificial lamb, damn it, I’m your brother!” Go on, read!

Let’s be clear from the start: There were just two siblings, my brother and me. We didn’t have a sister, much less a slutty one, as your hero suggested in his book. Musa was my older brother, his head seemed to strike the clouds. He was quite tall, yes, and his body was thin and knotty from hunger and the strength anger gives. He had an angular face, big hands that protected me, and hard eyes because our ancestors lost their land. But when I think about it, I believe he already loved us then the way the dead do, with a look in his eyes that came from the hereafter and with no useless words. I don’t have many pictures of him in my head, but I want to describe them to you carefully. For example, the day he came home early from the neighborhood market, or maybe from the port, where he worked as a porter and handyman, toting, dragging, lifting, sweating. Anyway, that day he came across me while I was playing with an old tire, and he put me on his shoulders and told me to hold on to his ears, as if his head were a steering wheel. I remember how ecstatic I felt while he rolled the tire along and made a sound like a motor. His smell comes back to me too, a persistent mingling of rotten vegetables, sweat, muscles, and breath. Another picture in my memory is from the day of Eid one year. He’d given me a hiding the day before for some stupid thing I’d done and now we were both embarrassed. It was a day of forgiveness, he was supposed to kiss me, but I didn’t want him to lose face and lower himself by apologizing to me, not even in God’s name. I also remember his gift for immobility, the way he’d stand stock-still on the threshold of our house, facing the neighbors’ wall, holding a cigarette and the cup of black coffee our mother would bring him.

Our father had disappeared ages before, reduced to fragments by the rumors of people who claimed to have run into him in France, and only Musa could hear his voice. He’d give Musa commands in his dreams, and Musa would relay them to us. My brother had seen him again only once since he’d left, and from such a distance that he wasn’t really sure it was him anyway. As a child, I knew how to distinguish the days with rumors from the days without. When my brother Musa would hear people talk about my father, he’d come home, all feverish gestures and burning eyes, and then he and Mama wo

uld have long, whispered conversations that always ended in heated arguments. I was excluded from those, but I got the gist: For some obscure reason, my brother held a grudge against Mama, and she defended herself in a way that was even more obscure. Those were unsettling days and nights, filled with anger, and I recall my panic at the idea that Musa might leave us too. But he’d always return at dawn, drunk, oddly proud of his rebellion, seemingly endowed with renewed strength. Then my brother Musa would sober up and fade away. All he wanted to do was sleep, and so my mother would get him under her control again. I’ve got some pictures in my head, they’re all I can offer you. A cup of coffee, some cigarette butts, his espadrilles, Mama crying and then recovering very quickly to smile at a neighbor who’d come to borrow some tea or spices, moving from distress to courtesy so fast it made me doubt her sincerity, young as I was. Everything revolved around Musa, and Musa revolved around our father, whom I never knew and who left me nothing but our family name. Do you know what we were called in those days? Uled el-assas, the sons of the guardian. Of the watchman, to be more precise. My father worked as a night watchman in a factory where they made I don’t know what. One night, he disappeared. And that’s all. That’s the story I got. It happened in the 1930s, right after I was born. That’s why I always imagine him gloomy, wrapped up in a coat or a black djellaba, crouching in some dim corner, and silent, without so much as a single answer for me.

So Musa was a simple god, a god of few words. His thick beard and strong arms made him seem like a giant who could have wrung the neck of any soldier in any ancient pharaoh’s army. Which explains why, on the day when we learned of his death and the circumstances surrounding it, I didn’t feel sad or angry at first; instead I felt disappointed and offended, as if someone had insulted me. My brother Musa was capable of parting the sea, and yet he died in insignificance, like a common bit player, on a beach that today has disappeared, close to the waves that should have made him famous forever!

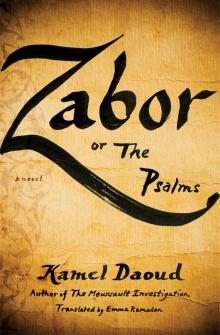

Zabor, or the Psalms

Zabor, or the Psalms The Meursault Investigation

The Meursault Investigation